The coronavirus is making data collection very much more difficult – admittedly a minor inconvenience in the greater scheme of things – so as a community of scholars we’re all learning how to do research in this new context. My physical science colleagues are slowly finding themselves back in labs with social distancing procedures and big facilities like Birmingham’s free air carbon enrichment site (BIFoR FACE) are getting back up to speed. As human geographers, we’re adapting to new ways of doing research mainly through online platforms. Indeed, some very dedicated people in the wider human geography community have been working hard putting together resources for undergrads wanting to continue with their dissertation data collection online over the summer. Tess is staying in my spare room for a few weeks while visiting the UK from the Netherlands. We’ve taken advantage of being locked in a house during her quarantine to do a bit of collaborative fieldwork that requires us to physically be in the same space. For some kinds of research, embodied presence is the only practical option, although this is somewhat ironic since we’re doing some work on virtual reality. We’ve just got a commission from Bristol University Press to do a ‘short’ book exploring VR methods for social sciences and humanities researchers. This will mean pulling together a critical review of how different scholars have used VR within their research projects and how it might be more widely employed. The book will also use worked examples from research that some of the Masters students in the Playful Methods Lab have been doing – with those individuals getting a co-author credit on a collaborative volume. One section of the book is looking at ‘readymade’, commercial VR experiences, including gaming. To this end, we’ve been thinking about the practicalities of doing content analysis in VR. This has involved getting myself and Tess together in a room while playing Half-Life Alyx, the first large scale, triple-A grade game designed exclusively for VR. Neither of us are big fans of horror games – I spent an alarmingly high proportion of my time playing 2014’s Alien: Isolation hiding in virtual cupboards feeling utterly terrified. As a result, neither of us have played the other games in the Half-Life canon. Nonetheless, Alyx works as a standalone game and so we felt it would be possible to undertake a content analysis on it, even though we’re not familiar with the wider story in which it sits. VR can be a very physical medium – depending on the hardware being used you can stand up and walk around, wave your arms, crouch and peer around corners. For the content analysis we therefore decided that it was important to film what we were doing, rather than just take written or voice notes so that we captured this physical interaction. Thus, we have footage recorded of the 3m by 2m area that we were using to play in, the size of the space being dictated by the constraints of my lounge and the length of the wire on the VR headset. We set up the camera so that it captured a secondary output from my gaming laptop being sent to my TV. Thus, our video field notes contain a view of the action seen by the player, as well as our physical movements and commentary on the experience. Alyx is quite an unusual experience for a player used to traditional consoles because the game environment is so interactive. You can bend down and pick up objects with your hand and throw them. You can punch through glass panes, pick up pens and draw on whiteboards. You reach out and grab door handles to pull them open. Even the action of closing a car door – which looks very boring on screen – feels almost magical.  The sense of immersion is the major selling point of VR but in a horror game this can be somewhat unpleasant. Oozing slime on walls, which looks unremarkable when seen on a TV screen, is viscerally disgusting when viewed through the headset. Dark passages seem horrifyingly ominous as you move your hand to point a virtual torch to illuminate pitch-black spaces filled with unknown dangers. Worse of all are the combat sequences. You start to panic while struggling to remember how to remove a spent magazine from your gun and reaching over your shoulder retrieve a new one from your virtual backpack. This can lead to running out of bullets and trying to duck out of the way of a creature that is jumping at your face intent on murdering you. Our experience of using VR is that it is reassuring to have someone else in the room who can tell you when you’re about to trip over something and generally look after your physical body while your senses are immersed in the virtual world. As a result, we’ve been taking it in turns to play, maybe doing about 40 minutes at a time. This also helps in terms of keeping a field diary – because the VR experience is so immersive it’s hard to maintain a commentary as you play because it’s very easy to forget you’re an academic doing research, rather than a survivor fighting off horrifying creatures in dank sewers. Having someone else there to ask you questions and prompt you to reflect on what’s happening is very helpful. We have, however, found Alyx utterly exhausting, even when taking turns to play. The sheer physicality of the experience, with heart rate and adrenaline constantly through the roof has meant that we haven’t spent as long playing as we had planned. Thus, we’re only about 5 hours in to a ~15 hour game and are both finding ourselves making excuses for “not playing today”. Both of us have found it emotionally draining and at times really quite distressing. This not only has methodological implications for content analysis but also, from an ethical point of view, for the kinds of VR experiences that one might choose to expose participants to. All of which, of course, is good material to reflect on as we begin work on writing the new book. If everything goes to plan, that book should be available in early 2022.

0 Comments

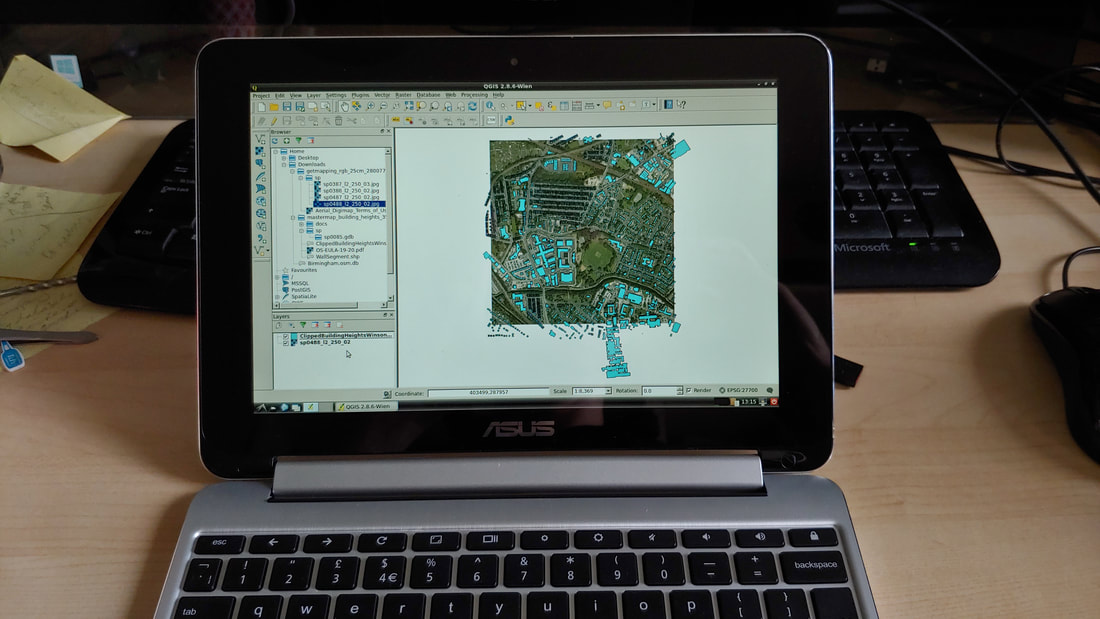

Recently I’ve been helping with the process of reworking our curriculum in response to the current restrictions. Among other things, am going to be running our new Year 1 GIS module designed around a blended learning approach. Even assuming that campuses are open in the autumn, we’re going to have restricted numbers of people in classrooms and many students will choose not to come to campus at all for safety and other reasons. This creates some challenges if, like us, you have somewhat old-fashioned GIS courses based in campus computer labs using site licenced ArcGIS. What can students do when working from home? Even if we were able to give out licence codes like sweets, it wouldn’t be practical to ask students to run ArcGIS on their own laptops. Some don’t have laptops at all. Meanwhile, although many of our students at Birmingham do own laptops, an unscientific survey of logos visible during lectures suggests that about half use Apple Macs. It’s technically possible to install ArcGIS on a Mac if one is prepared to set it up to also run Windows. Mac users tend, however, to be exactly the sort of people who have no interest in messing about with virtual machines or dual booting – they’ve bought a Mac because it just kinda works. So we need a different solution. For those who own a laptop, QGIS is a free, open source alternative to ArcGIS and is fairly platform agnostic, running across Windows, MacOS and Linux. Although QGIS is quite well developed, I’m not a huge fan of open source generally – I think it tends to cater to those who are passionate about computers rather than the majority of people who aren’t really that interested. Whenever I teach computing-related things, I always try to remember the students who struggle with even the basic principles – far too often you see a small but significant minority who get stuck with something as simple as moving or unzipping a file. There is no getting away from the fact that I’m a massive nerd, but I do like to try out doing things the hard way in order to figure out what’s the easiest way to do it. As an example, some of our students buy Chromebooks – and why not, they’re cheap, simple and reliable. Can you install QGIS on one? Yes… but. You have to install Linux in a custom shell and then install QGIS within that: As a result, even my ancient Chromebook with an underpowered ARM processor, can run a full desktop GIS so long as you’re willing to mess about with developer mode and the command line. Doing this sort of thing is my idea of fun. But there’s no way I’d suggest anyone but the most nerdy should attempt this and it’s certainly not something I’d ask my students to do.

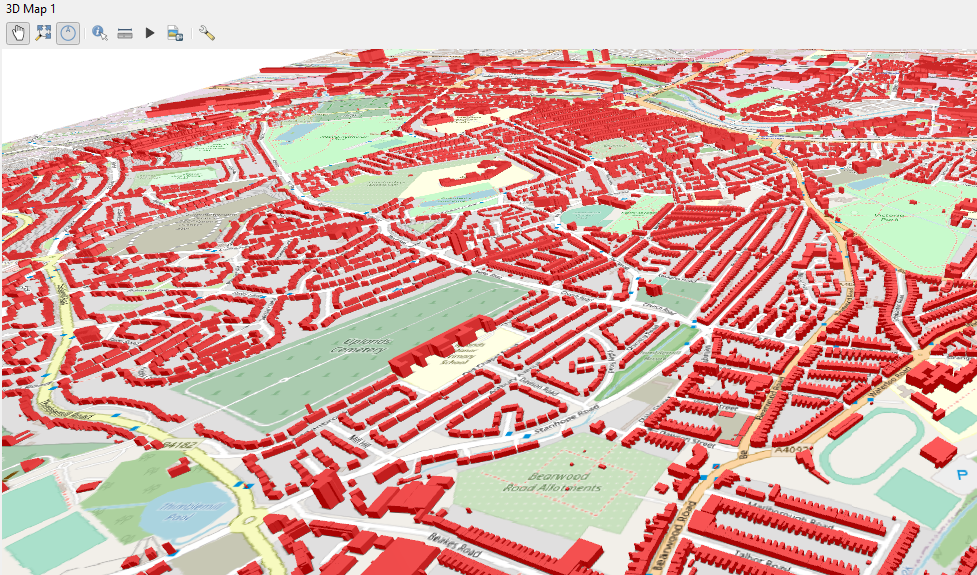

The upshot is that I’ve been developing some new GIS teaching working on the principle that some of our students will be using ArcGIS as normal and some will be using QGIS on their own machines and some won’t have access to a computer at all. At Birmingham our lives are made a bit easier by having a relatively wealthy cohort of students, most of whom have their own PC. But it’s important to consider those students working remotely with nothing more than a mobile phone (likely with limited data), so I’ve been thinking about how we can make using GIS more of a team exercise with students working in their tutorial groups. Thus, I’m designing elements for the module that need nothing more than a smartphone. This can be as basic as using Google Maps, or undertaking basic data collection using a simple app like Ramblr. There are even opportunities to do more complex data collection creating your own attribute tables using something like SW Maps on Android. The students will work their way through different GIS exercises using different tools – accepting that not all will be able to access everything. They’ll then collaborate in tutorial groups to design a map-based project that they can work on together – assuming a range of skills and access to technology. This might mean that one person crunches data in QGIS while another does some field data collection and someone else hunts out interesting secondary data sources. It’s not perfect, but it scales out quite nicely to a point in the future where, hopefully, they all have equal access to campus computing resources and software again. Oh and why am I going to teach both QGIS and ArcGIS when it would be simpler just to move everything to QGIS as the open source evangelicals would demand? The short answer is because it would be totally unfair to ask our IT team to undertake the major task of installing QGIS on machines across campus at a moment when they’re struggling just to keep the basic infrastructure functioning for remote working. Maybe next year…  Lockdown has affected people very differently. Some are having to homeschool their children. Some have less-than-supportive partners and so are picking up a greater share of the domestic burden. Some are trapped in cramped dwellings with no space to work. Others are really struggling with anxiety and isolation. All of this and more is shaping how those of us in the academic sector are able to work through the current crisis. Unsurprisingly given our fundamentally unequal gender relations, lockdown has seen the proportion of academic journal articles being submitted by a lead female author drop significantly. As someone without children, living in a comfortable, spacious home with a dedicated study, I find myself feeling a great deal of guilt that, because of my exceptional privilege, in many ways I’ve not really noticed the lockdown. During the summer period it is not that unusual for me to work from home four or five days per week and so this has not personally felt like a particularly jarring change of circumstances. Indeed, in common with many other single male academics, this seems a lot like a period of study leave, allowing me to get on with long-put-off writing projects and grant applications, while less fortunate others contemplate the damage this is doing their careers. Beyond research it’s also a time to pause, and reflect on some of my teaching practice. Our students have just handed in the substitute work I’d set them to replace the Berlin fieldcourse assignment. They’d been planning their field research projects for the ten weeks after Christmas leading up to our intended visit. When it became clear we would not be able to go this year, many chose to keep with the same topic but switched to a desk-based study because they couldn’t collect primary data in the field. Having marked my share of these, it’s a real shame we didn’t get to go because the groups had developed some really fantastic projects. It would have been incredibly interesting to see how well they could have operationalised these when dealing with the messiness of real world field practice. Nonetheless, it has got me thinking about what our students can now do in terms of desk-based projects, particularly considering that it’s going to be a while before we can allow traditional field-data collection to take place. Over the years of going to Berlin I’ve become interested in how we can find traces of previous layers of history within today’s landscape. I’ve blogged previously about Albert Speer’s plans for Germania, which was intended to completely remake the city as a kind of turbocharged fantasy of imperial Rome. On previous fieldcourses I’ve sent students off to hunt for the fragments of this scheme that remain in the landscape. Of the Neue Reichskanzlei, for example, not a trace remains except for some of the marble which was re-used to build the Soviet War Memorial at Treptower Park. Hitler’s personal palace was too badly damaged and too closely associated with the man to be preserved. Google Earth is a tremendous resource for geographers not least because of its time slider which allows you to look back at previous aerial photographs of a site to look for changes over time. For the most part this covers the last 20 years or so, but for some cities there are older image records. Berlin currently has three sets of historic air photographs available, taken in 1943, 1945 and 1953 respectively. In 1945 the Neue Reichskanzlei is still visible on Vossstrasse, if partly obscured by an overlap between the original photosheets. By 1953 the site is a blank, with just a ghostly outline of the reflecting pond in the rear gardens visible. More interesting in some ways is Teufelsberg, or the Devil’s Mountain. This is an artificial hill on the western edge of the city, which was a dump for demolition rubble after the war as bomb damaged buildings were cleared. An abandoned Cold War era listening station sits on top of the hill today, heavily graffitied and a popular site for alternative tourism. Less well known is the fact that this location had been prepared before the war ready for the construction of the Wehrtechnische Fakultät, a technical university which was to form part of a redevelopment cluster in the west of the city, close to the site of the 1936 Summer Olympics. Construction had started on one of the central buildings, sticking closely to Speer’s model for stripped classicism on a gigantic scale. Contemporary photos showed the shell of the building was significantly advanced before the war brought construction to an end. The building wasn’t particularly associated with Nazism and, had it been complete, it probably would have continued to have been used, just as the contemporaneous Air Ministry and Tempelhof airport complex were. Rather than demolish or finish it, the occupying powers chose simply to bury the ruined shell under the rubble coming out of the city centre. It is left as a tantalising object for future archaeologists. A virtual field visit using Google Earth allows us to get some sense of the building. Unfortunately, the 1940s air surveys don’t extend as far out as the nearby Teufelssee lake from which the artificial mountain would later gain its name. The 1953 survey does, however, clearly show the castle-like structure still standing and unburied. The measurement tools in Google Earth allow us to work out its size – just under 1.5 hectares (around 3.4 acres) – which makes it easier to get a sense of it scale. For those who know the University of Birmingham, it covers about the same amount of ground as the Aston Webb semi-circle at the heart of campus. Like the Aston Webb, this single building was to have been the centre of a much larger complex. Again, Google Earth allows us to easily get a sense of proximity to contemporary developments in Berlin, with the Wehrtechnische Fakultät just 1.6km away from the southern gate of the Olympic stadium with a direct axis to link them together. Of course, it would be fun to physically go to the site with a mobile device and use GPS to work out how much of the outline of the building could be walked around in what is now a heavily wooded location. Nonetheless, one can still gain some really interesting insights into these locations even when one cannot visit them. Covid-19 is changing the way that we think about travel and going different locations meaning that even when things return to ‘normal’ our practices for fieldwork will need rethinking. In the future, more and more of the work our students do will involve this kind of gathering materials online. Such activities will allow students to think through the types of data collection that require their physical presence in a location and those where a virtual visit will suffice. This will allow for much more efficient and effective use of our limited time in the field.

Note For more information about the Wehrtechnische Fakultät written in English, there is an interesting blog post here: https://flowersforsocrates.com/2016/12/31/structural-substitution-and-the-logic-of-urban-modernism/ I was supposed to be travelling to Berlin on Sunday with 135 undergraduates. Clearly, the current situation with Covid-19 has meant that we cancelled the trip as part of our preparations for what is likely to be quite a long period of campus shut down and remote working. It has to be said that our students have been incredibly supportive and understanding of the need to change our working patterns, including around fieldwork – for which we’re all really grateful.

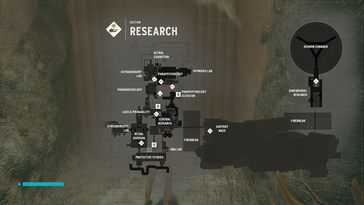

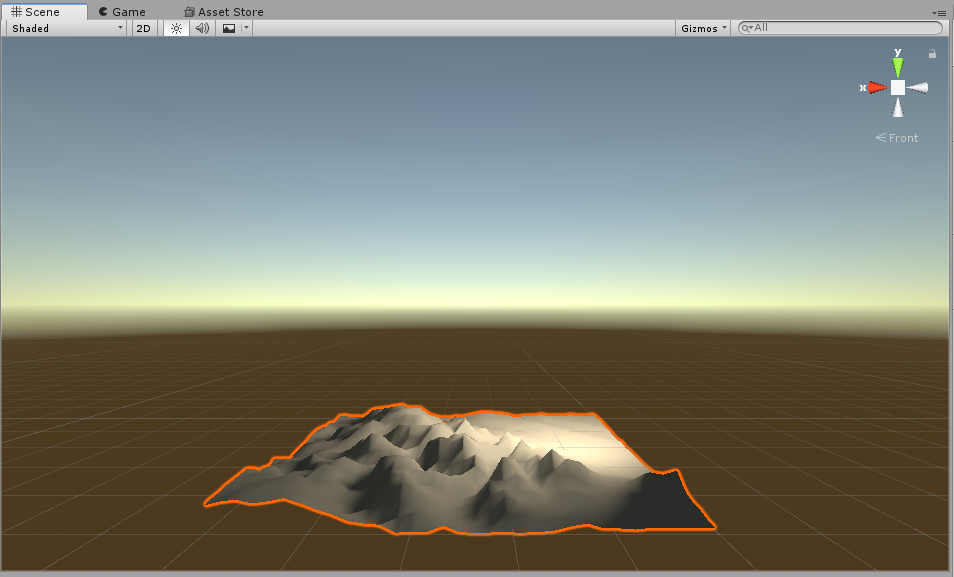

Although we aren’t going to Berlin in 2020, this does seem like a good opportunity to reflect on our undergraduate fieldcourse programme and some of the changes myself and colleagues at Birmingham have been making. Particularly since the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) was introduced in 2017, some of the top UK universities have been grappling with the question of added value: why should undergraduates come to a research-focused institution, rather than universities where staff spend a much higher proportion of their time on teaching. Even prior to the TEF, I have been very keen on the idea that instead of referring to undergraduate students we should be talking about undergraduate researchers. For me the advantage of coming to a research-focussed institution isn’t the snob value of attending a traditionally ‘top’ university with high entry grades and it certainly isn’t because of vague phrases around “teaching from research”. Of course, students do like it when we talk about research that we’ve been doing ourselves and it makes them feel connected to work at the cutting edge. But we can push this a bit further by emphasising the idea that the undergraduates are themselves part of a research community. Right at the start of my career in the early noughties I quickly got very bored marking the same essay over and over again. Thanks to a conservatism drummed in at school that there is a single “right” answer, students simply reproduced versions of my lecture notes. As a result, I altered my assessment strategies. Teaching urban regeneration at the time, I started forcing students to find their own case studies to use in their essays, drawing on media sources, web searches and even field observations of sites they knew from home. Suddenly the essays got a whole lot better, with students starting to get excited about taking the ideas they were learning about in class and thinking about how they could apply them to their own research. And, yes, I learned new things too. Since then, I’ve been keen to employ this research-led approach to undergraduate work wherever possible. For years our fieldwork was stuck in a bit of a rut. We took the students to the same places year in, year out, giving them the same sources to read (or, more likely, ignore) and saying the same things in the same sites. This inertia tends to happen when you have quite a high staff turnover (as we used to at Birmingham) meaning that people get dumped with a fieldcourse at the last minute and don’t have time to design something new. One of the things I’d always been really impressed with at other institutions like Manchester was fieldwork opportunities where the whole first year cohort was taken to a single location. This gave an opportunity for a year group to develop a bit of a collective identity. I’d also been interested in how we could use economies of scale to enhance our field teaching while keeping costs manageable. In 2017 we hatched a plan to bin all of the existing first year fieldcourses and move to a single trip. This gave us an opportunity to do an overseas visit for the same cost per head as we were spending on our UK trips – slightly greater expenses on the coaches vs. a substantially cheaper (and nicer!) hostel in Rotterdam. The Netherlands is a great location for a first ‘overseas’ fieldcourse since while locals speak pretty good English, culturally it’s quite a different place which can be very stimulating for the students. What we didn’t want to do, however, was simply create another ‘show-and-tell’ fieldcourse in a new location. Instead, students now spend the first five weeks of term learning about research methods and project design. This cuts across human and physical geography as well as planning. Groups of 20 students are then allocated to a member of staff who divides them into smaller teams, takes them out to some field sites and asks them to develop their own small research project – thinking up a research question, collecting and analysing relevant data before coming to some tentative conclusions. This approach completely changes the mindset of students entering the field as they become active researchers. It also reinforces the independent research mentality which is developed by those who do the Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) at A-level and gives a chance for those who haven’t done the EPQ to get up to speed. In the setup lectures I really emphasise the importance of failure as a learning tool – allowing them to get out of the A-level mindset of having to get everything right first time. By embedding small research projects throughout the curriculum – starting with the Rotterdam fieldcourse in their sixth week of university – the idea of doing a dissertation in year 3 suddenly seems a lot less intimidating. This year I had redesigned the setup for our year 2 Berlin trip to build on this model. Students were given ten weeks to design a research project that they were going to implement in Berlin. Teams met with their group leaders fortnightly to pitch their ideas in semi-formal presentations, showcasing their developing thoughts, the reading they’d undertaken and the work they had done to set up interviews and other activities in advance of travelling to the city. The overall Berlin trip was going to be for 135 students which is much easier to organise than the groups of up to 265 we’ve taken to Rotterdam! As a group leader, I was supervising 20 students, who had formed themselves into four teams doing four different projects. It was a real shame that they didn’t get to implement these in Berlin because they’d done an amazing amount of work in advance of the trip. There was a really interesting project looking at physiological response and wellbeing in relation to green space – with one team riffing off some research that I’ve been playing with for the last few years. There were a couple of groups doing really thoughtful projects in relation to memorialisation and the curation of memory. Finally, there was a group looking at the art-led gentrification of Neukölln who had created a map of all the new galleries that had opened there as well as having set up an interview with the district Mayor. Really great stuff. Even though we didn’t get to go to Berlin, the students I spoke to were very enthusiastic about having been given the opportunity to develop their own projects. Of course, the sneaky thing about all of this is that it’s not just about making ‘research’ part of the USP of studying at a research-focussed institution. It’s really about the independent critical thinking skills and teamwork that they develop through doing this kind of work so that they have really valuable things to talk about in job interviews. Because, let’s be honest, no matter what sector they end up working in, employers are going to be less impressed by students’ grasp of poststructuralist theory and much more interested in how well they can independently deliver on a project task.  Game map from Assassins' Creed Unity (Ubisoft, 2014) Game map from Assassins' Creed Unity (Ubisoft, 2014) Untitled Goose Game (House House, 2019) has, with good reason, featured in many critics’ Game of the Year lists. An utterly charming game, wrought in delicate pastel colours with wonderful sound design, one gets to play as a goose, waddling around an idealised English village, causing low level mischief and mayhem. I cannot emphasise strongly enough how playing this game makes the world a nicer place – not least because the controller has a dedicated button for honking. One of the cleverest elements of the game is its map, which one encounters at quite a late stage in your adventures. Maps have become absolutely crucial to modern gaming in part simply because of the sheer size of the landscapes that are now being made available for players to interact with. Without a map it’s all too easy to find yourself wandering around aimlessly, unable to find elements of the environment that are crucial to the game. The most recent episode in the long running Assassins’ Creed series AC: Odyssey (Ubisoft, 2018) creates an improbably vast world of approximately 233 square kilometres, all of which can be accessed and explored. The map allows the player to simplify and know this enormous game landscape, just as maps do in the real world. Of course, geographers have long critiqued maps, partly because of their militaristic origins and association with conquest and partly because the map reduces complex social and environmental characteristics to a series of highly simplified representations. Indeed, the choice of which things to represent and not gives the map maker significant power over that landscape – something that Denis Wood and others were discussing three decades ago. The more recent games in the Assassins’ Creed series have given players maps taking the form of a miniature 3D model, which can be zoomed and panned. This gives a godlike view over the game landscape as a whole, increasing the sense that this territory is yours to be conquered. Such a view is deliberately missing from Dear Esther (The Chinese Room, remastered version 2017) the original ‘walking simulator’ where players encounter a story told as they walk through a landscape. The designers left hidden messages in the shape of the landscape as a whole, but these can only be seen when editing it in a games engine. To the average player, lacking the god’s eye view of the designers, these messages are simply unreadable, a secret briefly teased in the game’s Director’s Commentary.  Game map from Control (Remedy, 2019). Game map from Control (Remedy, 2019). Players have very few choices about where to walk within Dear Esther – it’s pretty much a set of linear passages – meaning that a map overview wouldn’t really add anything to the gameplay. For most games, however, maps are crucial tools and it becomes very clear when a map is poorly designed. One of the other critically acclaimed releases of last year Control (Remedy, 2019) gives players a remarkable, absurdly large, brutalist building to walk around. For fans of Twin Peaks and David Lynch more generally, Control is a quite wonderful experience as one attempts to get to the bottom of a set of mysteries wrapped up in the stifling bureaucracy of a US government agency. The map is, however, next to useless for working out how to locate yourself within the sprawling complex being depicted. Indeed, one of the main comments made by gamers has been the ease with which one gets lost and disorientated in Control because the map is so poor. Given that the story of the game emphasises a sense of dislocation this is not entirely inappropriate, but it is more a question of weak design rather than intent.  Visiting the model village in Untitled Goose Game (House House, 2019) Visiting the model village in Untitled Goose Game (House House, 2019) This brings us back to Untitled Goose Game. It’s a puzzle and stealth game, where the player has to figure out how to do things like throwing a rake in a lake, all while avoiding being shooed away by irritated residents of the village. In its final sequence, you find yourself exploring the model village within the village – and, yes, the model village does have a model of the model village in it. This is a really clever bit of game design as it plays with the idea that we need a map to make sense of game landscapes. By wandering around the model village, we gain an overview of the village as a whole which, prior to this point, has been experienced in isolated pieces. The final mission involves taking an object from the model village back to the goose’s home, navigating carefully through the entire village while its residents try to stop you. Thus, exploring the model village builds the player’s mental map for undertaking the final sprint across the village as a whole. It’s a very canny bit of design. I won’t spoil the ending, which does have a laugh out loud moment. Even if you ignore its clever approach to mapping, however, buying and playing the game will definitely make your life better. Who doesn’t want to be a horrible goose in a lovely village? Reference Wood, D & Fels, J 1993 The power of maps Routledge, London. I’ve been greatly inspired by Bob Stone’s work here at Birmingham, particularly in how he and his team make reconstructions of historic landscapes for use in virtual reality. I’ll confess to having been a bit frustrated over the last few years because I could think of a whole lot of different projects I could do with this technology, but haven’t had the skill to do it myself. As a result, one of the tasks I set myself for the first quarter of 2019 was to learn a bit of Unity. For those who don’t know, Unity is a games engine, a piece of software that allows you to make video games of your own design. Although its higher functions require some skill at coding, Unity comes with a whole load of readymade code ‘prefabs’ from which you can build a game with little or no programming expertise. My friend and collaborator Tess Osborne has said she needs to get a T-shirt that just reads “Have you tried Googling it” to wear when teaching undergraduate IT classes. This is the approach I took to learning the very basics of Unity – skimming through other people’s blogs, messageboard posts and YouTube videos to find answers to different challenges I encountered along the way. I can’t imagine anyone would be interested in the details of this (you can drop me a line if you are) so I’m going to concentrate here on the outputs. I’ve done two small projects thus far: Germania and I have a dream. Both are very different expressions of how grand, triumphal cityscapes can be thought about. They currently exist as developer-only models for use in the Oculus Go – a portable, standalone headset that does not need to be tethered to a powerful computer. Germania was the name for Hitler’s planned redevelopment of Berlin, intended to be completed following the victory of Germany in WW2. A truly massive complex of new buildings in a stripped-down classical style would have been assembled on a north-south axis through the heart of the existing city. The crowning glory was to have been the Volkshalle, a 290 metre tall domed building. The ludicrous scale of this development is hard to put across. I’ve borrowed a pre-existing digital model of part of the planned development, rescaled and fiddled with it and put it into a navigable landscape in VR. My colleague Lloyd Jenkins has been in Berlin this week with the students, standing in the location close to the Reichstag where the Volkshalle would have been built in the real Berlin. They’ve had a go at standing in the real landscape while navigating the virtual landscape of the unbuilt project to get a sense of the sheer scale of that unbuilt plan and what that says about the mentality that underpinned its design.  We’ll be using the Germania model next week as part of an AAG workshop organised by Tess along with Danielle Drozdzewski and Jacque Micieli-Voutsinas. Participants will stand in the National Mall in Washington DC, giving them the opportunity to contrast Hitler’s vision in the VR headset with the material reality of one of the landscapes that inspired his architect Albert Speer. This will allow participants to examine questions of scale and intimidation in the architecture of dictatorship as well as to reflect on the spatial qualities of the 1902 McMillan Plan for Washington DC. I’ve also built a simplified recreation of the National Mall for VR that will allow workshop participants to stand in a virtual Mall listening to Martin Luther King giving his I have a dream speech. Again, the idea is to reflect on the difference between physical and virtual presence in the real present and an imagined past. It’s been quite fun working out some of these ideas – Tess and I have been asked to write some of this up for a forthcoming book emerging from next week’s workshop. It’s also been a useful process in thinking through what some of the possibilities for using this technology in teaching and research can be – I’m a great believer in learning by doing. Even if I’m never going to be an expert in the use of these technologies, learning the basics is a great way to have meaningful conversations with potential collaborators over much more sophisticated applications. VR has been the next big thing for a very long time. Back in 1993 confused TV audiences in the UK got to see Craig Charles hosting Cyber Zone – a short-lived attempt to bring VR to the masses. Cyber Zone sticks in my mind mostly because one of the challenges involved navigating around Cyber Swindon, the real version of which my parents moved to the following year. In recent years large technology firms have revisited the idea of VR as dramatic advances in processing power, sensor technology, screen resolution and refresh rates have allowed for the creation of a much more convincing immersive experience. Facebook (owners of Oculus), HTC, Microsoft, Samsung and others have all had a swing at VR with varying degrees of success. Although the tech is considerably more advanced than in the 1990s it still feels somewhat unrefined and very much a solution in search of a problem. I’ve got a VR setup that I use for demonstrations, open days and the like. Assetto Corsa, a racing sim, looks graphically unremarkable when viewed on a screen but seen through a headset it’s really quite compelling. Indeed, using the headset in combination with a full steering wheel and pedal set, I’ve ‘driven’ the course of Trento-Bondone, a 17km hill climb. I ended up every bit as exhausted as the time I drove up a switchback alpine road to Breil-sur-Roya north of Nice. Admittedly driving my virtual Fiat 500 the course took me over 22 minutes, compared to the lap record of 9 minutes but it was sufficiently convincing that when I finally reached the end of the course I ‘stopped’ the car and automatically reached for a handbrake that wasn’t there. So how does this involve my parents? Well, a few months ago I discovered that Google Earth is now available in VR and had a play around. It made me think about a conversation I’d had with my mother where she talked about the fact that her knees were starting to play up which meant there were hill walks she could no longer attempt. I wondered whether VR would be a good substitute allowing people to visit spaces they could no longer access. Virtual flying up to the top of the Old Man of Coniston in the Lake District was quite satisfying for me because of the several times I’ve climbed that hill I’ve never actually seen the view from the top because of low cloud. The view in VR seemed to me to be really quite convincing. Maybe there’s a project here, I thought to myself. Heading up to see my parents in December, I packed up some of my VR gear to get them to have a play with Google Earth. My parents are both from Liverpool originally and moved back to the north west a few years ago. I gave both of them a go in the headset, starting from Liverpool and, in my mother’s case, also having a virtual walk around Coniston. While neither of my folks are massively techy, they do enjoy playing with Google Earth on their computers, my mum in particular using it to have a look at places she reads about. Neither of them were therefore taken aback by the existence of Google Earth itself but both were very surprised by how different it feels when you are in those virtual landscapes rather than just looking at them on a screen. I had my mum walking around a little whilst in the headset – I’m using a Samsung Odyssey which has camera-based motion tracking – though this can be quite awkward because it’s easy to get tangled up in the wires and you can feel rather wobbly and disorientated. She was quite delighted at being a giant able to walk across a miniaturised central Liverpool. Less convincing for her was the virtual climb up Coppermines Valley in Coniston. The closer you get to the ground surface in Google Earth, the more it becomes obvious that it’s a somewhat pixelated aerial photograph. As she later told me, when she goes for a walk, for her it’s not about the view from the top, it’s about the detail of the flowers and grass right next to her. My mother had initially struggled a bit getting to grips with the controls to fly around the virtual environment, so I spent a little more time explaining them to my father before he put the headset on. Immediately he started zooming down the Old Dock Road in Liverpool and I assumed he’d very quickly get disorientated but within about ten seconds he’d got complete control over his virtual movements and was happily flying across Liverpool giving a guided tour to us both. When he was younger, he was a flight instructor for gliders – a fact I must admit I’d not thought about when I put him into the headset. Talking through the experience he said that he’d immediately felt that he was in an aircraft and that the controls, involving tilting the controller up and down, had felt incredibly intuitive. Later he took great delight in flying underneath the Runcorn bridge and then landing his virtual plane at Speke airport – or Liverpool John Lennon as it is now known – just round the corner from where he grew up.

It was a really interesting afternoon that got me thinking about the intersection of virtual landscape, memory and experience. I think there’s a project to be done there, but it still needs a bit of pondering. Possibly this will involve building a smaller, but more detailed environment of the kind that Bob Stone’s team have been doing for years. Admittedly my initial efforts to learn Unity last week in order to do this have not progressed very quickly, though I’ll admit I was childishly delighted to create a walkable ‘landscape’ based on a crude import of terrain data for Snowdonia. If I get any further along with this I’ll write another post… Just as we are heads down in the final run to the end of term and Xmas I've finally managed to regain access to my website after several months of password-based shenanigans. What better way to celebrate than to upload the piece that I intended to post at the end of the summer about eye tracking... One of the things I promised myself while I was in Australia was that I would hack together an inexpensive eyetracker this summer that I could give my students to play with. What I’ve done is buy a Tobii 4C – basically a toy that is designed to be used with certain video games to pan the screen around via eye movement. This cost me £121 on Amazon. It’s a small bar that attaches to the bottom of your screen and plugs into your computer via USB. All the clever stuff is done onboard the eyetracker itself (which is essentially a camera that can see your eye movements) so it will run very happily on a low-powered laptop. Tobii explicitly prevent you from using their API to capture the datastream from this device so that you can’t use it to record the raw eyetracking data for research purposes. This is fair enough given that a lot of people who don’t need clinical grade eyetracking would probably find this device ‘good enough’ and thus not pay the hefty subscriptions to use Tobii’s more accurate equipment and software. Tobii do, however, allow you to create a representation of your eye movements across the screen using their ‘Ghost’ software from which you can undertake what we might refer to as descriptive eye tracking. You can then connect this to streaming software (they recommend OBS Studio) which can either record or live-stream what you see on your screen to services like Youtube and Twitch. Thus you can record a video with an eyetracking overlay showing the researcher what their participants were looking at when viewing the screen. This can work with movies, games, websites, or simply a collection of images in PowerPoint. In the image below you can see me playing around with a heatmap style representation of where I’m looking on an image of a fantasy city. In no way is this good enough for doing advanced psychological work. Indeed, such a set up would be rightly dismissed as ‘descriptive’ by anyone who works in this field. It is, however, quite cute and a cheap way of showing the principles and possibilities of work using this kind of technology. And sometimes ‘descriptive’ work is good enough to highlight potentially interesting research questions that you might want to investigate through other means. I used this setup at the RGS ‘Digital Landscapes’ event co-organised by my excellent PhD student Tess Osborne in August. Again, it’s more about starting a conversation than doing anything approaching ‘science’ with this kind of tool. I've since given it to the third year students taking my Geographies of the Body module to see what projects they'd come up with. They've done some quite cool stuff looking at representations of London and New York in cinema, a project looking at Asian beauty standards and a comparaison of green versus white (snowy) space. It’s very exciting seeing what the students come up with when you give them the opportunity to play around with different methods – a point I made at our last open day when I was getting applicants (and their parents!) to play with this eyetracking set up, as well as a VR driving experience.

A few years ago when I was running the Human Geography Research Theme at Birmingham with my colleague Julian Clark, we sat down to try and cook up a way of reintroducing study leave. Although the University’s procedures for this were still in place, as a School it had largely stopped except where people had secured a fellowship to buy out their teaching.

Julian and I introduced a system whereby colleagues could coordinate with us and with the programme leads to make space for taking a semester out to have study leave; other research themes in the School subsequently copied our system. Obviously, because I’d helped re-introduce study leave I thought it would look far too self-interested if I tried to go on leave myself right away. But fast forward a few years and having secured a Universitas 21 travel grant, I found myself in a position to have my first period of study leave in the 15 years that I’ve worked at Birmingham. The time I’ve spent in Melbourne has been tremendously productive. The School of Geography at the University of Melbourne is an excellent department, with some really top-class scholars. Melbourne as a city has a number of other really good universities, so there’s a fantastic intellectual climate here. I am immensely grateful to all the people who’ve taken the time to meet with me and particularly to Birmingham’s International Office for making the U21 funding available to come here.

For the U21 Fellowship I worked on projects around map collections, the management of interdisciplinary urban studies and the potential for running an undergraduate fieldcourse to Melbourne. But I’ve also had targets to achieve for my Head of School and College. I had forgotten the simple joy of simply sitting down, undisturbed, writing without email pinging, without admin tasks to do and without people knocking on your door. I’ve not had that experience since I finished my PhD in 2003. Things that might otherwise have taken me months to finish off have been turned around in matter of days.

Obviously, there’s a lot to be reflected on here in terms of decluttering academic life and trying to resist the fragmentation of time that has become a major part of the job these days. As a colleague here put it “slow down to speed up”. Indeed, since my study leave started in January, I’ve written two grant applications, the case for support for a third, I’ve been assembling the manuscript for an edited book, done the corrections on a paper that has since been accepted and even, in the last few days, drafted a book proposal. On one level, then, I’m nervous about returning to the normal academic fray once I get back to the office in Birmingham in a week or so. But on other levels, I have missed my colleagues and my students. There’s a lot of fun and satisfaction to be had in those other parts of the job away from the secluded cloisters of study leave. Nonetheless, it’s been a hugely productive couple of months for me that will doubtless show up as a purple patch in my CV. The challenge facing many departments in the UK is in making sure everyone is able to maximise their opportunities for developing ideas, researching and writing alongside their other responsiblities. Defragmentation of time and protection from mundane and routine tasks is the only way to make this a part of the everyday academic experience. As I’m coming to the end of my stay in Melbourne, I’m going to take the opportunity to reflect on some ideas I’ve been having about the possibilities for geographers presented by eye tracking technology.

In collaboration with Jodi Sita from the Australian Catholic University, I’ve written a grant proposal while I’ve been here which seeks to use eye tracking glasses to examine how cyclists engage with urban spaces. These glasses overlay a record of where you’re pointing your eyes onto a video recorded from a front facing camera mounted at eye level. These devices used to be a little Heath Robinson, but are now very slickly packaged with a similar weight and appearance to sports sunglasses, making them suitable for field-based use. Meeting with a couple of eye tracking specialists while I’ve been here has given me the chance to think through some ideas around how geographers can engage with these technologies. The majority of work in eye tracking is lab-based, asking participants to look at a screen and recording how long they spend looking at different elements of images displayed on the screen. Again, this used to be a technology that was very expensive and complex, but which has tumbled in price and rocketed in usability over the last few years. Jodi has just published an edited collection looking at what eye tracking can bring to film and TV studies. I had a fascinating conversation with Angela Ndalianis of Swinburne University of Technology about her collaboration with Jodi examining some of the assumptions made by film studies scholars about how audiences watch movies – what elements filmmakers intend to draw the eye vs. the parts of the screen that audiences actually look at. A fascinating opportunity to debunk some long-held theories and confirm others. Jodi has also run an amazing project examining how people respond to green space, showing them film of walks through parks to see what elements they pay attention to in the landscape. In conversation with Adrian Dyer at RMIT, he revealed his concerns that a great many studies being undertaken with eyetracking these days (not including those described above) are insufficiently rigorous and overly descriptive. This is doubtless a fair point. But there’s something about this moment with the technology that allows for research to emerge that might not meet the standards of rigour of conventional approaches to eye tracking, but which can nonetheless give new insights into a variety of different areas. One can buy a basic screen-based eye tracker for less than £200, although this unfortunately lacks the specialist software that allows you to do the automated analysis. That specialist software gets quite expensive quite quickly – about €2500 for a year’s subscription – but allows you to start identifying how much time people spend examining different elements within an image. At high levels of sophistication, eye tracking can give insights into people’s decisionmaking. Market researchers use this to determine things like how the design of packaging can make people more or less likely to buy a product (there’s a group at Monash working on this). One of the things I intend to do when I get back to the UK is see if I can hack together something relatively crude to allow students to do basic analysis using a cheap gaming eye tracker. From a scientific point of view, this would be entirely without rigour, but for demonstrating the principles of how one could start to use this technology, I think it could be very useful. Once something usable falls below £1000, however, I can see that there would be serious interest among geographers in what this technology could do. Scholars working on, for example, place, mobilities, landscape etc. could gain some fascinating new insights working with these techniques. |

AuthorPhil Jones is a cultural geographer based at the University of Birmingham. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Phil Jones, Geographer

The INTERMITTENTLY updated blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed