|

VR has been the next big thing for a very long time. Back in 1993 confused TV audiences in the UK got to see Craig Charles hosting Cyber Zone – a short-lived attempt to bring VR to the masses. Cyber Zone sticks in my mind mostly because one of the challenges involved navigating around Cyber Swindon, the real version of which my parents moved to the following year. In recent years large technology firms have revisited the idea of VR as dramatic advances in processing power, sensor technology, screen resolution and refresh rates have allowed for the creation of a much more convincing immersive experience. Facebook (owners of Oculus), HTC, Microsoft, Samsung and others have all had a swing at VR with varying degrees of success. Although the tech is considerably more advanced than in the 1990s it still feels somewhat unrefined and very much a solution in search of a problem. I’ve got a VR setup that I use for demonstrations, open days and the like. Assetto Corsa, a racing sim, looks graphically unremarkable when viewed on a screen but seen through a headset it’s really quite compelling. Indeed, using the headset in combination with a full steering wheel and pedal set, I’ve ‘driven’ the course of Trento-Bondone, a 17km hill climb. I ended up every bit as exhausted as the time I drove up a switchback alpine road to Breil-sur-Roya north of Nice. Admittedly driving my virtual Fiat 500 the course took me over 22 minutes, compared to the lap record of 9 minutes but it was sufficiently convincing that when I finally reached the end of the course I ‘stopped’ the car and automatically reached for a handbrake that wasn’t there. So how does this involve my parents? Well, a few months ago I discovered that Google Earth is now available in VR and had a play around. It made me think about a conversation I’d had with my mother where she talked about the fact that her knees were starting to play up which meant there were hill walks she could no longer attempt. I wondered whether VR would be a good substitute allowing people to visit spaces they could no longer access. Virtual flying up to the top of the Old Man of Coniston in the Lake District was quite satisfying for me because of the several times I’ve climbed that hill I’ve never actually seen the view from the top because of low cloud. The view in VR seemed to me to be really quite convincing. Maybe there’s a project here, I thought to myself. Heading up to see my parents in December, I packed up some of my VR gear to get them to have a play with Google Earth. My parents are both from Liverpool originally and moved back to the north west a few years ago. I gave both of them a go in the headset, starting from Liverpool and, in my mother’s case, also having a virtual walk around Coniston. While neither of my folks are massively techy, they do enjoy playing with Google Earth on their computers, my mum in particular using it to have a look at places she reads about. Neither of them were therefore taken aback by the existence of Google Earth itself but both were very surprised by how different it feels when you are in those virtual landscapes rather than just looking at them on a screen. I had my mum walking around a little whilst in the headset – I’m using a Samsung Odyssey which has camera-based motion tracking – though this can be quite awkward because it’s easy to get tangled up in the wires and you can feel rather wobbly and disorientated. She was quite delighted at being a giant able to walk across a miniaturised central Liverpool. Less convincing for her was the virtual climb up Coppermines Valley in Coniston. The closer you get to the ground surface in Google Earth, the more it becomes obvious that it’s a somewhat pixelated aerial photograph. As she later told me, when she goes for a walk, for her it’s not about the view from the top, it’s about the detail of the flowers and grass right next to her. My mother had initially struggled a bit getting to grips with the controls to fly around the virtual environment, so I spent a little more time explaining them to my father before he put the headset on. Immediately he started zooming down the Old Dock Road in Liverpool and I assumed he’d very quickly get disorientated but within about ten seconds he’d got complete control over his virtual movements and was happily flying across Liverpool giving a guided tour to us both. When he was younger, he was a flight instructor for gliders – a fact I must admit I’d not thought about when I put him into the headset. Talking through the experience he said that he’d immediately felt that he was in an aircraft and that the controls, involving tilting the controller up and down, had felt incredibly intuitive. Later he took great delight in flying underneath the Runcorn bridge and then landing his virtual plane at Speke airport – or Liverpool John Lennon as it is now known – just round the corner from where he grew up.

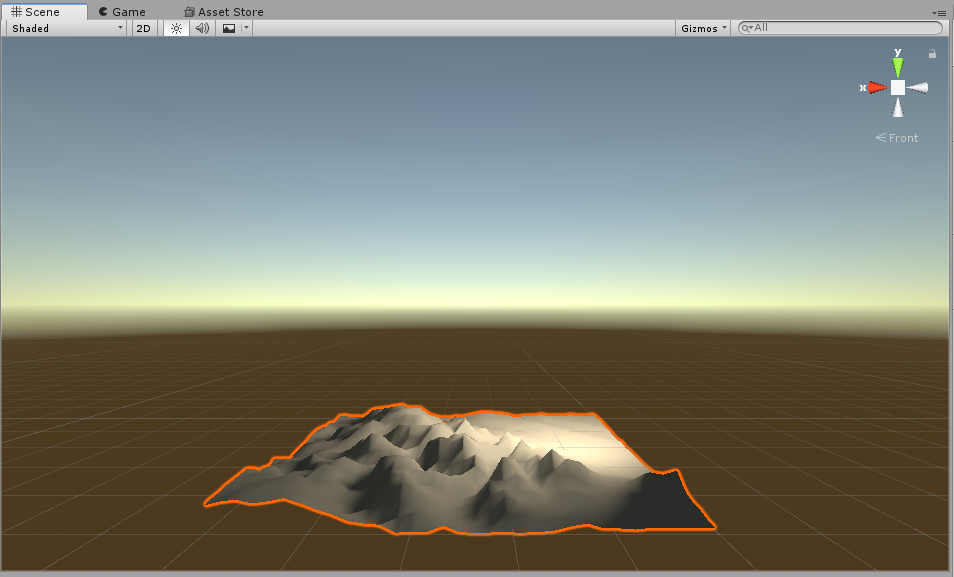

It was a really interesting afternoon that got me thinking about the intersection of virtual landscape, memory and experience. I think there’s a project to be done there, but it still needs a bit of pondering. Possibly this will involve building a smaller, but more detailed environment of the kind that Bob Stone’s team have been doing for years. Admittedly my initial efforts to learn Unity last week in order to do this have not progressed very quickly, though I’ll admit I was childishly delighted to create a walkable ‘landscape’ based on a crude import of terrain data for Snowdonia. If I get any further along with this I’ll write another post…

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPhil Jones is a cultural geographer based at the University of Birmingham. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Phil Jones, Geographer

The INTERMITTENTLY updated blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed