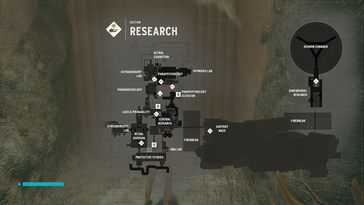

Game map from Assassins' Creed Unity (Ubisoft, 2014) Game map from Assassins' Creed Unity (Ubisoft, 2014) Untitled Goose Game (House House, 2019) has, with good reason, featured in many critics’ Game of the Year lists. An utterly charming game, wrought in delicate pastel colours with wonderful sound design, one gets to play as a goose, waddling around an idealised English village, causing low level mischief and mayhem. I cannot emphasise strongly enough how playing this game makes the world a nicer place – not least because the controller has a dedicated button for honking. One of the cleverest elements of the game is its map, which one encounters at quite a late stage in your adventures. Maps have become absolutely crucial to modern gaming in part simply because of the sheer size of the landscapes that are now being made available for players to interact with. Without a map it’s all too easy to find yourself wandering around aimlessly, unable to find elements of the environment that are crucial to the game. The most recent episode in the long running Assassins’ Creed series AC: Odyssey (Ubisoft, 2018) creates an improbably vast world of approximately 233 square kilometres, all of which can be accessed and explored. The map allows the player to simplify and know this enormous game landscape, just as maps do in the real world. Of course, geographers have long critiqued maps, partly because of their militaristic origins and association with conquest and partly because the map reduces complex social and environmental characteristics to a series of highly simplified representations. Indeed, the choice of which things to represent and not gives the map maker significant power over that landscape – something that Denis Wood and others were discussing three decades ago. The more recent games in the Assassins’ Creed series have given players maps taking the form of a miniature 3D model, which can be zoomed and panned. This gives a godlike view over the game landscape as a whole, increasing the sense that this territory is yours to be conquered. Such a view is deliberately missing from Dear Esther (The Chinese Room, remastered version 2017) the original ‘walking simulator’ where players encounter a story told as they walk through a landscape. The designers left hidden messages in the shape of the landscape as a whole, but these can only be seen when editing it in a games engine. To the average player, lacking the god’s eye view of the designers, these messages are simply unreadable, a secret briefly teased in the game’s Director’s Commentary.  Game map from Control (Remedy, 2019). Game map from Control (Remedy, 2019). Players have very few choices about where to walk within Dear Esther – it’s pretty much a set of linear passages – meaning that a map overview wouldn’t really add anything to the gameplay. For most games, however, maps are crucial tools and it becomes very clear when a map is poorly designed. One of the other critically acclaimed releases of last year Control (Remedy, 2019) gives players a remarkable, absurdly large, brutalist building to walk around. For fans of Twin Peaks and David Lynch more generally, Control is a quite wonderful experience as one attempts to get to the bottom of a set of mysteries wrapped up in the stifling bureaucracy of a US government agency. The map is, however, next to useless for working out how to locate yourself within the sprawling complex being depicted. Indeed, one of the main comments made by gamers has been the ease with which one gets lost and disorientated in Control because the map is so poor. Given that the story of the game emphasises a sense of dislocation this is not entirely inappropriate, but it is more a question of weak design rather than intent.  Visiting the model village in Untitled Goose Game (House House, 2019) Visiting the model village in Untitled Goose Game (House House, 2019) This brings us back to Untitled Goose Game. It’s a puzzle and stealth game, where the player has to figure out how to do things like throwing a rake in a lake, all while avoiding being shooed away by irritated residents of the village. In its final sequence, you find yourself exploring the model village within the village – and, yes, the model village does have a model of the model village in it. This is a really clever bit of game design as it plays with the idea that we need a map to make sense of game landscapes. By wandering around the model village, we gain an overview of the village as a whole which, prior to this point, has been experienced in isolated pieces. The final mission involves taking an object from the model village back to the goose’s home, navigating carefully through the entire village while its residents try to stop you. Thus, exploring the model village builds the player’s mental map for undertaking the final sprint across the village as a whole. It’s a very canny bit of design. I won’t spoil the ending, which does have a laugh out loud moment. Even if you ignore its clever approach to mapping, however, buying and playing the game will definitely make your life better. Who doesn’t want to be a horrible goose in a lovely village? Reference Wood, D & Fels, J 1993 The power of maps Routledge, London.

1 Comment

|

AuthorPhil Jones is a cultural geographer based at the University of Birmingham. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Phil Jones, Geographer

The INTERMITTENTLY updated blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed