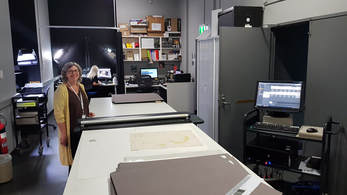

Maggie Patton showing off the digitisation facilities at the State Library of New South Wales Maggie Patton showing off the digitisation facilities at the State Library of New South Wales At the University of Birmingham we have a very large map collection held within the School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences. It’s an eclectic mix of maps used in the field, teaching sets of ordnance survey and geology maps, large scale topographic maps for regions across the globe, a treasure trove of historic items and fascinating oddities such as fire insurance plans. More and more of the everyday maps that we use for teaching are now digital, however. In common with map collections elsewhere in the UK the balance is therefore shifting from being a working collection toward being more of an archive collection. Archives are, of course, fantastically important and useful things – well I would say that, given that I used to be an historian – and so we’re looking at how we manage the long-term future of the excellent collection that we have at Birmingham. I’ve been in Melbourne for just over a month now and have been working on a number of projects in parallel. One of my reasons for being here is to look at Australian practice in terms of managing map collections. I’ve spent the last few weeks talking to experts in the field about how they manage their maps, having meetings with University-based map librarians and collection managers based at the Victoria and New South Wales State Libraries and the National Library of Australia in Canberra. In meeting this group of passionate and fascinating individuals, a couple of themes have become clear. First, as in the UK, university map librarians are starting to retire and when they do, institutions are having to make difficult choices about how they manage those collections. The library team at one university are currently doing a piece of research attempting to figure out what to do with what has become a somewhat orphaned collection. The library building in which it’s housed is under great pressure to expand the number of study spaces as student numbers climb meaning that storage space is at a premium. Some of the map material has been passed to other institutions, some will go to offsite storage, some may be disposed of. The future seems to be in digitisation – perhaps no surprise. Scanning maps is a lot of work, but in some ways is the relatively straightforward part of the problem. The key challenges would seem to be:

Fundamentally these are library and database management problems which means that securing the future of the collection at Birmingham will need much closer coordination with our central library team. There are a lot of things to put in place before we can start simply scanning the maps, even if we can get volunteer labour to help offset some of the costs of this. We also need to look carefully at what is already available online at archive grade before doing any scanning. The National Library of Australia, for example, get a great many inquiries from people in the UK because they’ve made freely available a great number of high quality scans of Ordnance Survey maps of Britain. There’s quite a bit of work for us to do at Birmingham, but from what I’ve seen operating here, I think we can be optimistic about securing the future of our collection. This will require an investment of time and money but, based on this trip, I feel much more confident in knowing what we need to ask for and who we need to talk to in order to make this happen. I need to say a big thank you to everyone who took the time to meet with me here in Australia, but particularly to David Jones, the Map Curator at the University of Melbourne who has been incredibly generous in opening up his little black book and connecting me with colleagues across the country. If you are interested in maps and find yourself in Melbourne, do look David up - he's a thoroughly good bloke and looks after quite an amazing collection.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPhil Jones is a cultural geographer based at the University of Birmingham. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Phil Jones, Geographer

The INTERMITTENTLY updated blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed